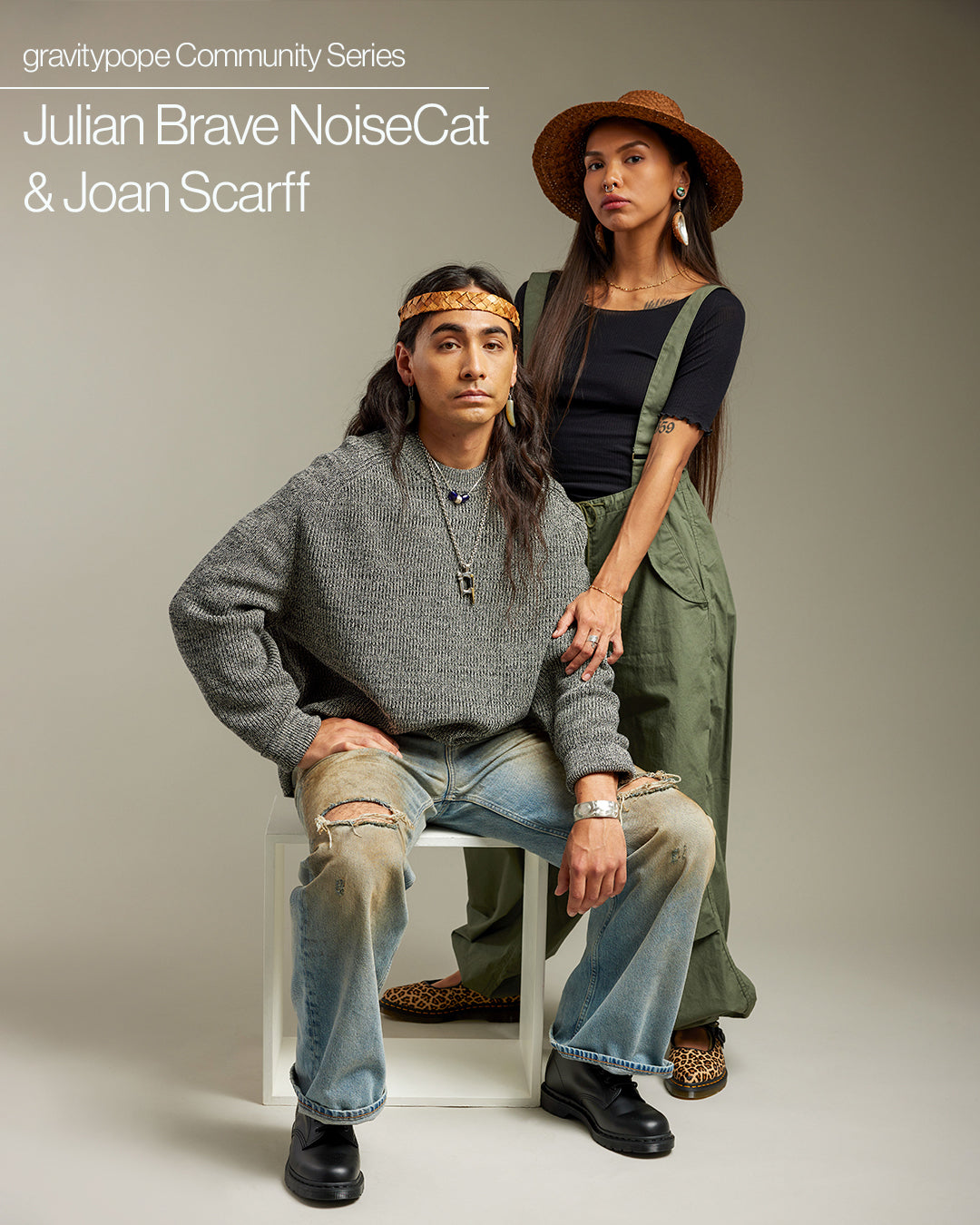

Julian Brave NoiseCat is a writer, filmmaker, and powwow dancer whose stories of contemporary Indigenous life have been recognized across mediums. A member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq'escen and descendant of the Lil'wat Nation of Mount Currie, he became the first Indigenous North American director to be nominated for an Academy Award in 2024, with Sugarcane, a documentary following an investigation into abuse and missing children at the Indian residential school his family was sent to near Williams Lake, B.C. In October, Penguin Random House Canada will publish his first book, We Survived the Night: An Indigenous Reckoning, a genre-bending work of creative nonfiction. His personal style reflects similar clarity of vision—pared back, intentional, and tied to place.

His partner, Joan Scarff, is a beader, seamstress, weaver, and youth worker hailing from four nations: Gitxaala, Nisga'a, Tlingit, and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh. Joan draws from Northern and Coast Salish lineages, thoughtfully and intentionally using pattern, negative space, and material tension to create pieces that are composed, exacting, and at once traditional and urban. The two share a thoughtful approach to how they present themselves and their work, deeply considered but never overworked.

gravitypope recently spent time with Julian and Joan to talk about where expression starts—whether through clothing, politics, or something slower, like beadwork.

Models own jewelry and accessories by:

Joan Scarff

Julian and Joan wear new arrival from Acne Studios, Dr. Martens, Studio Nicholson, Aspesi, A.P.C. Moma and more.

Read the full interview below.

Interview and Styling by: Amanda May Daly

Makeup by: Lou Lewis

What have you learned from each other’s creative processes?

Julian Brave NoiseCat (JBN): I learn so much just hanging out with Joan and her family. They’re from four coastal nations, including Gitxaała, so they’ve always got amazing seafood and when I’m lucky, Indian round steak (fried bologna). Joan works with Indigenous kids in inner-city schools, and her people are matrilineal. Because I’m a nomadic Secwépemc and St’at’imc writer/filmmaker/uncle working remote and often on the road, we end up spending most of our time together at her and her family’s place.

We talk about and make art in the living room. I try out different ideas and stories, and Joan shows me the dozen or so projects they always have going. And sometimes we influence each other. I’ve picked up a lot of style from Joan—every outfit I put on I’m trying to keep up with her, which is hard! The earrings Joan beaded for the Academy Awards riffed on a design from one of my great-great-grandmother’s baskets, which is tucked into a drawer at the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology. Those earrings are one of my most cherished possessions.

Joan Scarff (JS): Julian gives good input on outfits, bead colors, and project ideas (especially for him, lol). He remembers to write the good ideas down—even when he’s stoned. He’s not ajix (a picky eater) and loves all our food. He asks lots of questions. The way we go about things creatively and otherwise is different. And he tries to learn and speak Sm’algyax (Tsimshian). He knows a few funny lines now.

Julian wears: Studio Nicholson Coe Crewneck, Acne Studios 2021M Loose Fit Jeans, and Dr. Martens 1461 Mono.

Joan wears: Baserange Pama 3/4 Tee, Beams Boy US Army Overpants, Dr. Martens Elphie Mary Jane, and Acne Studios Platt Micro Shoulder Bag.

Julian, how has the reception of Sugarcane, your Oscar-nominated doc, impacted you and the story you're telling?

JBN: Sugarcane tells the story of how our families, communities, and people were torn from one another and our culture by colonization and the Indian residential schools and what that did to us and our way of life. It has made me think very purposefully about how I tell stories, make art, and live my life. I’m grateful for the way people—my own people, Indigenous people, non-Indigenous people—have received the film. With my forthcoming book, We Survived the Night, a work of narrative nonfiction about my family and our people that will be published by Knopf and Penguin Random House Canada in October, I want to account for and bring back what was taken from us.

Joan, how did your beadwork and jewelry practice start — what is your favourite aspect of this work?

JS: My great-grandmother gave my mom this floral beaded hairpiece when my parents first got together. Growing up I would always hold it and marvel at her work. It made me want to bead. In 2019, I finally invested in some supplies, met other beaders, and started making my own work. Since then, I have also picked up sewing, weaving, and tufting. Making art my friends and family wear brings me lots of joy. I love to see the expressions on their faces when they first try on a piece from me.

Julian wears: A.P.C. Ross Shirt, Studio Nicholson Yale Pant, and MOMA 2AW003 Derbys.

Joan Wears: Aspesi Long Dress, A.P.C. Greta Trench, and TORAL 12357 boots.

How do you support one another’s creative work — whether it's on a film set or at the beadwork bench?

JS: We eat traditional food as much as we can and laugh big together. Our creative processes flow from being grounded in family and community but also being adventurous when the wind calls. We love visiting, resting, and looking at art. We try to find things or experiences that fill our cups—usually relatives, other Natives, and each other.

JBN: It’s hard being on the road away from family and loved ones so much, especially when I was out there sharing such a heavy personal story about genocide. I’m grateful when I get breaks to visit Joan and her family, who always have yummy fish, some China Lilly, and a warm cup of coffee on the counter. She laughs big, I tease, and we nerd out. Sometimes it’s the latest work by Himikalas (Pam Baker) or another bad-ass Indian auntie. Sometimes it’s the stories of the trickster Coyote—a no-good but nonetheless legendary ancestral uncle anti-hero from my culture. And sometimes it’s Star Wars—an essential touchstone in the lore of Joan’s living room.

Working on narratives all the time, I end up thinking and living life like it’s a story. So, in my head, Joan and I are co-stars in an anime about urban Indigenous life called Coyote Boy & Raven Girl.

Julian, you're the first filmmaker Indigenous to North America nominated for an Academy Award, what has this process been like for you?

JBN: It was an incredible honor to be the first Native North American filmmaker nominated for an Oscar. But it’s outrageous that it took 97 Academy Awards ceremonies for an Indigenous North American filmmaker to be nominated. Our people have so many untold stories; we come from such deep and underappreciated cultures, and we have so much unseen and overlooked beauty to share with the world. I hope Sugarcane is part of the ongoing Indigenous renaissance encouraging other people to pay attention and our own people to hold our heads high as we continue to take back what’s ours.

What was your favourite part about stepping out on the red carpet with your family?

JBN: I’m so grateful I got to see my dad, Ed Archie NoiseCat, on the red carpet. He’s been the tricksterly icon at the center of so many of my life stories. It was huge to have the world see the legend who had such a big hand in shaping my life as the movie star he’s always been to me. Dad, Auntie Charlene Belleau, and Chief Willie Sellars all looked so regal on the red carpet. I’m really grateful to our stylist, Amanda May Daly from Vancouver, who helped us represent the best way we could.

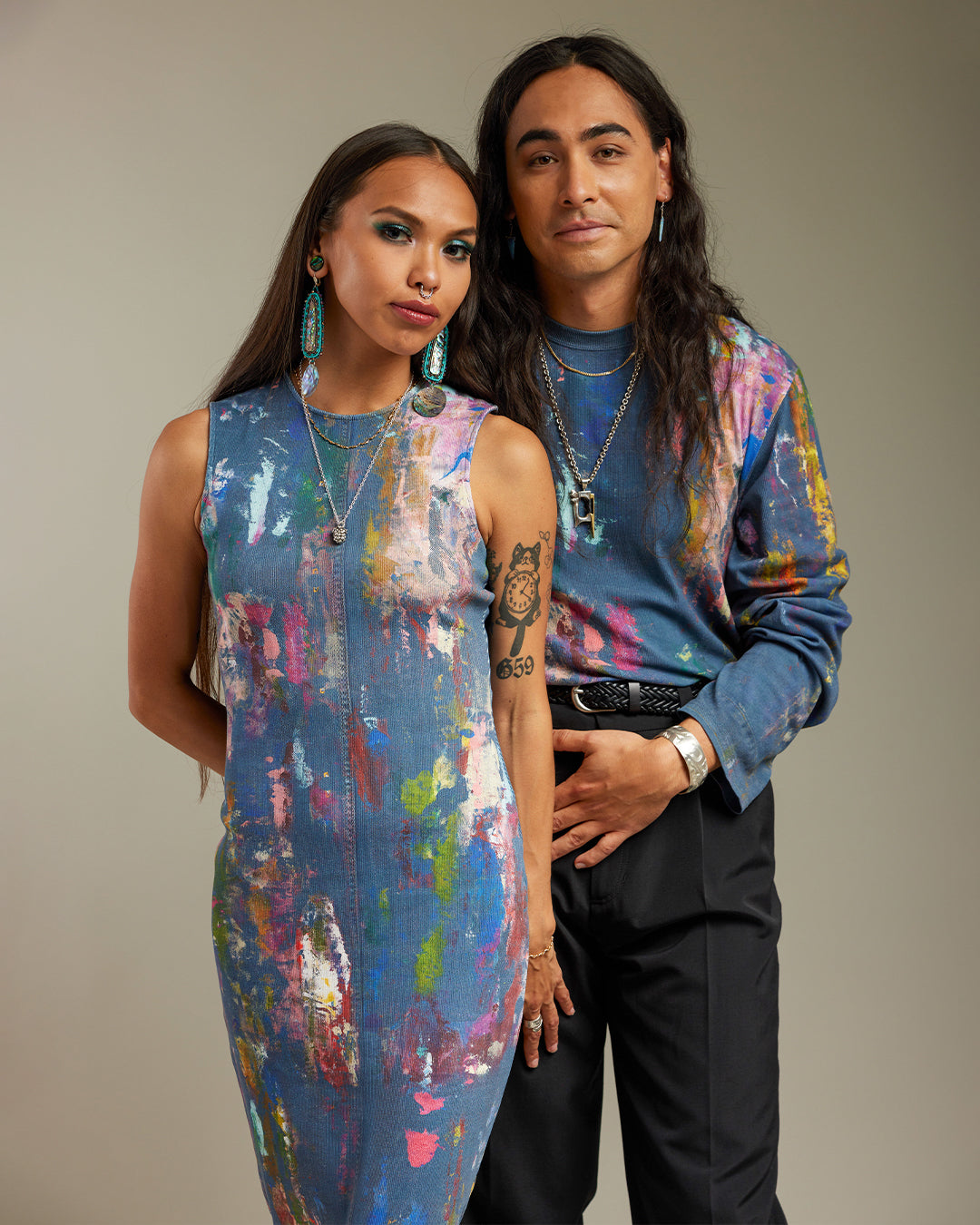

Julian wears: Acne Studios Long Sleeve T-shirt, Acne Studios Tailored Trousers, and MOMA 12502A Sneakers.

Joan wears: Acne Studios Midi Dress, and Chie Mihara Idan Mary Janes.

How do clothing and jewelry serve as forms of storytelling?

JBN: So often as Indigenous people, our clothing and jewelry are an outward expression of who we are and where we come from. For example, the centerpiece of my outfit for the Academy Awards was a moosehide vest made by my late Granny Lizzie gifted to me by Auntie Charlene. Granny Lizzie is now long gone and very few people still do that kind of hide and beadwork in our nation. Plus, those vests are usually reserved for leaders like our chiefs and councilors. It’s an honor to own and take care of one for my family and people. Whenever I wear it, you know I’m really trying to stunt. But also: stunting is a big part of our culture! With our clothing, our jewelry, our hair, our aesthetic, our drip, etc. we’re always telling stories about who we are. Joan describes my aesthetic as Indian professor/artist/uncle, which is about right.

How would each of you describe your style — and how has it evolved over time and what does personal style mean to you?

JS: Inner city Indigenous with a neo-traditional twist. My style was influenced by my environment growing up and over time I’ve gotten bolder and more unapologetic about being Indigenous and two-spirit. My outfits say: “I’m here, Indigenous, and queer.”

JBN: My style is always changing, probably because I travel across worlds so often—different parts of Indian Country, the white world, the film world, the publishing world, the hockey locker room, etc. I try to dress in a way that fits the expectations of the space I’m in while pushing its boundaries in ways that feel true to me. For most of Sugarcane, for example, I was doing a more classic Western look because the men in my family are cowboys going back a few generations. So, I’d show up to events with all these New York and LA people looking professional but rocking cowboy boots and wranglers with a pearl snap, some earrings, and a headband, or something like that. More recently, I’ve been hanging with Joan and doing a more urban look to try to keep up with their alt queer aesthetic. It’s not easy because Joan is so stylish. Plus, I don’t have any tattoos or unusual piercings, so my hair and jewelry, and the fit, drape, and colours of my outfits have to be on point or I look like a scrub. It’s a fun challenge.

How do you blend traditional elements with modern silhouettes or trends?

JS: I base all of my outfits on my traditional pieces. If I have a pair of earrings I want to wear, the whole outfit is planned around highlighting and matching the earrings. Or looking at how I can blend parts of my regalia with an outfit to bring that extra flare. I don’t think people realize how so many trends can be elevated by adding the right pieces from our Indigenous cultures.

JBN: I think menswear gets a little less attention in fashion, probably because for too many men being fashionable is seen as feminine. But Native men have style. A lot of us wear our hair long; we rock long earrings, necklaces, and other jewelry. Whenever I get dressed, I’m trying to find ways to make whatever I’m wearing look cool and Indigenous. I want other Indians to see me across the room, especially if we’re cousins who haven’t visited in a minute. And I want non-Indigenous people to wake up and realize how alive and dope Indigenous peoples are right now—not 200 years ago.

When selecting clothing for major events, how do you balance style with symbolism? What are the messages you try to convey through what you wear?

JBN: I treat major events like I would a powwow, ceremony, feast, or any other cultural gathering. What I wear has to have some relation to my peoples, my communities, and my families. It needs to tell a story, because that’s what I do for a living. But I interpret that in a way that is both traditional and modern. If my stories and travels have brought me into relation with people who have gifted or otherwise made things I am proud to wear, then I feel like that can be just as much a part of my look as a moosehide vest from my family.

What advice do you have for people who want to wear Indigenous fashion respectfully?

JS: Buy directly from Indigenous people, make sure to remember the name and nation of the artist. It’s a huge thing in Indigenous communities to share where you got your piece from. It’s like bragging rights if you have a piece from a well-known artist and a conversation starter over who is your fav beader. It’s also cool to have things from artists in your area—the territory you’re on. That being said, it’s best to stay away from ceremonial regalia. And don’t be afraid to ask questions! Native artists like me love talking about and sharing things.

JBN: I think people should wear things that speak to them and help tell their story, and if they feel like Indigenous pieces can do that for them—in a respectful way, of course—then they should feel comfortable supporting those Indigenous artists and their work. There are only so many Indians in the world and if we are the only ones buying and wearing our work, then our artists and designers will never get the visibility, recognition, and cultural impact they deserve.

What’s one piece in your wardrobe that holds a personal or significant meaning?

JS: My mother and I have matching red capes with our crest, the two-headed Raven, on it. I made them because our nation, Gitxaała, sang and danced for the opening ceremony of the All Native Basketball Tournament in Prince Rupert this year.

JBN: All my pieces mean something to me because they remind me of the people who made them or gifted them to me. I especially love all the pieces Joan, my dad, my mom, and my family have made for me because those pieces hold and remind me of their love.

Have there been any recent trends you’re excited by or inspired to reinterpret through your own cultural lens?

JS: I thrift a lot and would love to see more vintage old-time-y looks but Indigenous. The hippie aesthetic was modeled off Indigenous peoples, for example. We should reclaim it.

JBN: I have this theory that all of our aunties and uncles looked deadly in the 1970s. If you walk into any Indian household in North America, there will be a photo of someone’s mom or dad or pé7e (grandfather) or kyé7e (grandmother) or maybe all of them all in one frame looking like real life movie stars in denim jackets, cowboy hats, loud collared shirts, wranglers, belt buckles, and boots with the hair and those head-turning features and probably a cigarette in hand. People overlook just how cool that era was—Red power, the American Indian Movement. Cultural pride looks good on our people. Which is to say we shine when we love one another and ourselves.

Are there any new spring clothing or shoes you currently have your eye on?

JS: I have my eyes on the A.P.C. Gustav Jean and the Dr. Martens Church Quad boot.

JBN: Joanie is my forever aesthetic inspiration and also low-key my in-house stylist and fashion critic. So you should listen to her!

We’re excited to swing by Gravity Pope, try on stuff, and walk out the door with new pieces for the summer. It’s rare to find a place with such a wide selection of great looks. I wear something from the shop almost everyday.

Who are some Indigenous creatives or designers you’d love to spotlight?

JS: Himikalas (Pam Baker) – Touch of Culture (TOC) Legends, Heather Dickson – DicksonDesigns, Shelly Samuels – Yasakw Yakgujanaas Design.

JBN: I want to shout out some incredible Indigenous creatives and designers who have helped me tell my story over the past few months in the lead-up to and aftermath of the Academy Awards: Jennifer Younger, Himikalas (Pam Baker) – Touch of Culture Legends, Caitlin Hein – He Sapa Vintage & Garbage Tale Vintage in Rapid City, South Dakota, Angel Aubichon – IndiCity, Randi Nelson, Naiomi Glasses x Polo Ralph Lauren, Calina Lawrence of the Suquamish Tribe in Washington, Decolonial Clothing Co. in Vancouver, B.C., Peshawn Bread – House of Sutai, Son of Picasso – Products of My Environment, Maakarita Paku – Tribal Fibres, Jeanine Clarkin (the godmother of Māori streetwear), Tayla Hartemink – program artist for Māoriland Film Festival 2025, Vashti Etzel, Unorthodox Yukon & the Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon, Relative Arts in NYC, Joey Montoya – Urban Native Era, my dad Ed Archie NoiseCat, my stylist Amanda May Daly, and of course: Joanie.